|

| That's not an expedition... |

|

| THIS is an expedition! (Central Asiatic Expedition near the Flaming Cliffs) |

At one time vast expanses of the world's maps were blank and labeled "here be dragons," but by the early twentieth century, most of those blank spots had been filled in. One exception was the vast Gobi in Mongolia, which was still a place of mystery to westerners.

And it was to this last frontier that the AMNH sent an ambitious expedition led by one of the greatest American explorers of the twentieth century: Roy Chapman Andrews (1884-1960).

|

| Andrews in the Mongolian badlands |

In his spare time, Andrews, already an experienced taxidermist, assisted in the collection and preparation of specimens, and he took advantage of every opportunity to learn and make himself useful while pursuing a Masters degree at Columbia University. His persistence paid off and he began to work officially as a collector for the museum - one of his first jobs was the logistically difficult task collecting and preparing a beached whale (a specimen that remains on display in the Museum to this day), which needed to be accomplished before the corpse rotted too badly to be useful.

Andrews was a larger than life figure, and he needed to be: after persuading AMNH president, Henry Fairfield Osborn to launch the Gobi expedition, Andrews was told that he would have to raise the money himself. In those days science was not supported with government funding and a successful scientist had to be adept at securing donations from wealthy philanthropists. Andrews needed $250,000 to get started, and by the end was able to secure about $5 million in current dollars from some of the wealthiest tycoons in American society including J.D. Rockefeller and Cleveland Dodge, who supplied automobiles for the expedition.

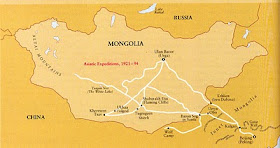

One of the largest and most ambitious scientific ventures of its day, the AMNH's Central Asiatic Expedition, as it came to be known, consisted of five treks, between 1921 and 1930, from their field headquarters in Peking into Inner and Outer Mongolia. The journeys were fraught with danger because of the 1912 fall of the Manchu Dynasty, which left China destabilized until Mao Ze Dong's rise to power in the 1940's. The expedition had the support of the Chinese government in Peking, but warlords ruled the provinces and cared little for letters of transit or other documents issued in Peking.

The situation in Mongolia was also volatile as Outer Mongolia became an independent state in 1921, and Russian Bolsheviks and Czarists battled for influence there and frequently came into conflict with the Mongols, who were, at the time, also trying to fend off territorial expansion by the Chinese. This instability resulted in a lawlessness that encouraged widespread banditry.

In one particular instance while Andrews was driving he was attacked by mounted Mongol bandits. Realizing he'd never get his car turned around in time to escape, he elected to attack, driving straight into the charging bandits with his six-shooter blazing. This was typical of Andrews who was nothing if not a decisive man of action.

|

| Out looking for trouble |

These character traits, which suited him so well as an expedition leader in a lawless land was sometimes a liability in the field, however. Though Andrews had earned his Ph.D. by this time he lacked the patience for painstaking fieldwork, usually preferring to gather his specimens by shooting them. His favourite field tool for fossil collecting was a pick axe, and such was his reputation for hasty collecting that, to this day, a fossil that is damaged by careless excavation is said to have been "RCA'd." I've been guilty of RCA'ing a specimen or two in my time as well.

The wealth of scientific information and specimens that were gathered are too numerous to list here, but among the discoveries were the very first fossil dinosaur eggs ever found, which were believed at the time to have been laid by Protoceratops, but are now known to be Oviraptor eggs.

|

| Unearthing dinosaur eggs |

When I'm doing field work I normally have a field pouch for my notebook and pencils, and a rock hammer hanging from my belt (and sometimes pepper spray, depending on the bear situation). Notice what Andrews has on his? A gun belt and ammunition.

Roy Chapman Andrews is generally regarded as the inspiration for Indian Jones and the similarities are hard to ignore:

George Lucas has never confirmed that Andrews was a direct inspiration in the creation of Indiana Jones, and it is entirely likely that he wasn't. However, Andrews was a very popular media figure in his day and the subject of many serialized adventures in books and movies. He'd been a member of the Explorer's Club since 1908, and served as its president from 1931-1935. So even if Lucas did not consciously base Indiana Jones on Roy Chapman Andrews, it is almost certain that the character was inspired by fictional heroes that Lucas grew up with who were direct representations of Andrews:

|

| Serial adventure hero based on Roy Chapman Andrews |

I think the world is a more exciting place when there are real-life pulp heroes to tread the jeweled thrones of the world beneath their field-booted feet.

Admittedly, that was intended to be an illustration of the party planning between adventures back at their "home-base" so they naturally aren't going to be carrying around everything they would out in the dungeon.

ReplyDelete