I've been spending most of the last two weeks painting up a unit of Warhammer High Elf Dragon Princes of Caledor for the GW Winnipeg store's display case. The set will be released on October 2nd, so here's a sneak peak:

The level of detail in these sculpts is amazing and they were a great deal of fun to paint, though very time consuming - especially the standard bearer, because free-handing the dragon was pretty fiddly.

Thursday, September 30, 2010

Wednesday, September 29, 2010

Dramatic License in Roleplaying

When I first started playing D&D I had very little background in fantasy literature to draw upon for inspiration. Aside from The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, I had only mythology to refer to, particularly Ray Harryhausen movies which I watched obsessively when I was a kid.

The famous skeleton fight scene from Jason and the Argonauts is one of my favourites, and I especially love how Jason and his lads were classy enough to let the evil wizard complete his ritual to animate the skeletons. This kind of appreciation of dramatic license is something one rarely sees in a roleplaying game. If this had been a D&D encounter I imagine it would have gone down something like this:

DM: "The wizard reaches into a clay pot that he is carrying under his arm and..."

Fighter: "I charge him!"

Dwarf: "I shoot him with my crossbow! I had it ready, remember?"

Cleric: "I cast hold person!"

Magic User: "Magic Missile....MAGIC MISSILE!!!"

DM: "sigh...Okay, roll for initiative."

Party Leader: "Oh, sweet...natural 20!"

Moments later...

DM: "Okay, the wizard has been held, blasted with arcane bolts, shot through the heart with a crossbow bolt, and cloven in twain by the fighter's greatsword. He slumps to the ground, dead."

I'm tempted, one of these days, to pull a Gran Torino ending and have the old man's clay pot full of alms he was distributing to the poor, or something. The angry mob of peasants hungry for PC blood might teach 'em a thing or two about dramatic license, damn their twitchy trigger fingers.

Monday, September 27, 2010

Session 10: The City of Tiers

After descending for days into the earth's depths, the switchbacks the party had been traversing finally opened into a 'forest' of mineral deposits growing up from the ground near the shore of a vast underground lake. In the distance, on the far shore of the lake lay Dragotha, a four-tiered city carved into a sloping cliff face.

The party passed through the high iron walls that protected the city after being questioned by suspicious gate-wardens, who directed them to a nearby tavern, Rock Bottom. The tavern was a panoply of species diversity: humans, dwarves, hobgoblins, and creatures the likes of which the party had never seen before. The bartender, a goblin named Salacious Lickspittle, quickly informed the party that their coins were valueless in Dragotha, but offered to hook them up with a man named Bartemius Foulstone who might be willing to exchange worthless topsider money for local Dragoons. The party, who only wanted to find a safe path back to the surface, realized that this might take longer than they hoped.

While they waited for Foulstone, the party cautiously sipped their suspiciously smoking drinks, which were distilled from the juice of local fungi. Theon poured some of his drink onto the stone table top and was alarmed when it started fizzing. One of the locals, overhearing the party's predicament, introduced himself as Tas, a 'trustworthy thief', unlike the despicable Bartemius Foulstone whom, he cautioned, would cheat and rob the party. Instead, he offered to change their topsider money at fair value.

The party accompanied Tas out of the tavern and were told to wait while he got them their money. Tas then proceeded to dart through the crowd, picking every coin purse he could lay his hands on. Sadly he was a bit too hasty slitting the purse of a large bugbear who was soon chasing Tas down the street bellowing in rage. Tas bolted back to the party, running through them and around the corner. The bugbear crashed into Bvar, knocking him flat then proceeded to smash him with a spiked club in frustration because, in the words of the famous minstrel, Stills, 'if you can't kill the one you're mad at, kill the one you're with.'

The enraged creature was prevented from causing further harm by a hold person spell quickly cast by Theon, who then tried to smooth things over with the bugbear, explaining that they were the victims of misunderstanding, and were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. As soon as the party left, Tas returned and filched the coin purse of the still held bugbear.

The party soon learned that Dragotha was a kleptocracy with each tier controlled by one of four rival factions. The highest and most prestigious tier was ruled by a mob boss called The Painted Man, while the third tier was run by The Leech Lord. The second tier was the domain of The Crone, while the lowest tier was run by a troll by the name of Septimus T. Squalor.

The party soon became embroiled in local politics when Salacious Lickspittle hooked them up with a man named Albinus the Pale, who might help them return to the surface in exchange for a small favour. Albinus worked for The Painted Man, who needed to insert some agents into Squalor's gang to kidnap a blind seer known as the Oracle. Since all of The Painted Man's men were known to Squalor's gang, strangers to Dragotha might have a better chance of getting close to the 'lord of the lower tier' without arousing too much suspicion. To facilitate this, Albinus had some of his men start trouble with orc mercenaries in Squalor's employ at a watering hole near Squalor's stronghold. The party stepped in on the side of the orcs and dispatched The Painted Man's men with all the panache of a staged fight orchestrated to show off their impressive fighting skills. The orcs were, indeed, impressed and agreed to introduce the party to their boss.

Septimus Squalor didn't achieve the lofty heights of ruling the lowest tier by trusting every man, orc, or goblin that knocked on his door looking for work, however, and he needed the party to prove themselves before allowing them into his employ. Squalor was interested in adding to his arcane power by collecting mystic adepts, such as the The Oracle who was kept leashed at his side. To further this, he instructed the party to kidnap the shaman of a tribe of morlocks who lived a short distance from the city and preyed upon unwary travelers in the Under Reaches.

With two orc lackeys to guide them, the party traveled to the camp of the morlocks. Tas scouted the camp and reported a band of about twenty degenerate cannibals whose shaman was about to sacrifice a bound captive and roast her. The party waited until the shaman's ritual was complete and was about to plunge his dagger into the chest of the captive before Theon attempted to cast hold person on him. The shaman passed his save easily and proceeded to cut out the heart of his victim and offer it on a heated brazier to his dark god. The party decided to settle this the old-fashioned way - close combat. They easily slaughtered the band of Morlocks but the Shaman held back and fled when things began to look 'iffy.' He ordered his followers to spend their lives to defend him, then he fled. Tas broke away from the battle to chase the shaman, only to be confronted by an albino ape that the shaman had freed from its cage and set upon his pursuer.

The shaman was eventually tracked down and subdued, then taken to Squalor. Having gained the trust of Squalor, I'd envisioned them waiting until everyone was asleep then trying to sneak the Oracle out, like the scene from Return of the Jedi, but the players decided on an altogether different approach: a frontal assault. Theon attempted his signature Hold Person spell on Septimus, which failed. Enraged by this treachery, Septimus attacked Theon. During the confusion Valkrys, the monk, threw the Oracle over his shoulder and ran for it. Some very poor Intelligence checks on the part of the orc guards on the subsequent levels of Squalor's Tower allowed Valkrys's feeble and thoroughly improbable bluffs ("Everyone up to the top level - Septimus is being attacked!") to succeed beyond all expectation.

The session ended with the party fleeing Squalor's tower, strung out in order of movement rate, with an angry troll crime lord and his entire gang in hot pursuit. The plan, if I might generously refer to it as such, is to get to the upper tier - The Painted Man's domain - with the Oracle before being caught and torn limb from bloody limb by a vengeful mob of criminals.

The party passed through the high iron walls that protected the city after being questioned by suspicious gate-wardens, who directed them to a nearby tavern, Rock Bottom. The tavern was a panoply of species diversity: humans, dwarves, hobgoblins, and creatures the likes of which the party had never seen before. The bartender, a goblin named Salacious Lickspittle, quickly informed the party that their coins were valueless in Dragotha, but offered to hook them up with a man named Bartemius Foulstone who might be willing to exchange worthless topsider money for local Dragoons. The party, who only wanted to find a safe path back to the surface, realized that this might take longer than they hoped.

While they waited for Foulstone, the party cautiously sipped their suspiciously smoking drinks, which were distilled from the juice of local fungi. Theon poured some of his drink onto the stone table top and was alarmed when it started fizzing. One of the locals, overhearing the party's predicament, introduced himself as Tas, a 'trustworthy thief', unlike the despicable Bartemius Foulstone whom, he cautioned, would cheat and rob the party. Instead, he offered to change their topsider money at fair value.

The party accompanied Tas out of the tavern and were told to wait while he got them their money. Tas then proceeded to dart through the crowd, picking every coin purse he could lay his hands on. Sadly he was a bit too hasty slitting the purse of a large bugbear who was soon chasing Tas down the street bellowing in rage. Tas bolted back to the party, running through them and around the corner. The bugbear crashed into Bvar, knocking him flat then proceeded to smash him with a spiked club in frustration because, in the words of the famous minstrel, Stills, 'if you can't kill the one you're mad at, kill the one you're with.'

The enraged creature was prevented from causing further harm by a hold person spell quickly cast by Theon, who then tried to smooth things over with the bugbear, explaining that they were the victims of misunderstanding, and were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. As soon as the party left, Tas returned and filched the coin purse of the still held bugbear.

The party soon learned that Dragotha was a kleptocracy with each tier controlled by one of four rival factions. The highest and most prestigious tier was ruled by a mob boss called The Painted Man, while the third tier was run by The Leech Lord. The second tier was the domain of The Crone, while the lowest tier was run by a troll by the name of Septimus T. Squalor.

The party soon became embroiled in local politics when Salacious Lickspittle hooked them up with a man named Albinus the Pale, who might help them return to the surface in exchange for a small favour. Albinus worked for The Painted Man, who needed to insert some agents into Squalor's gang to kidnap a blind seer known as the Oracle. Since all of The Painted Man's men were known to Squalor's gang, strangers to Dragotha might have a better chance of getting close to the 'lord of the lower tier' without arousing too much suspicion. To facilitate this, Albinus had some of his men start trouble with orc mercenaries in Squalor's employ at a watering hole near Squalor's stronghold. The party stepped in on the side of the orcs and dispatched The Painted Man's men with all the panache of a staged fight orchestrated to show off their impressive fighting skills. The orcs were, indeed, impressed and agreed to introduce the party to their boss.

Septimus Squalor didn't achieve the lofty heights of ruling the lowest tier by trusting every man, orc, or goblin that knocked on his door looking for work, however, and he needed the party to prove themselves before allowing them into his employ. Squalor was interested in adding to his arcane power by collecting mystic adepts, such as the The Oracle who was kept leashed at his side. To further this, he instructed the party to kidnap the shaman of a tribe of morlocks who lived a short distance from the city and preyed upon unwary travelers in the Under Reaches.

With two orc lackeys to guide them, the party traveled to the camp of the morlocks. Tas scouted the camp and reported a band of about twenty degenerate cannibals whose shaman was about to sacrifice a bound captive and roast her. The party waited until the shaman's ritual was complete and was about to plunge his dagger into the chest of the captive before Theon attempted to cast hold person on him. The shaman passed his save easily and proceeded to cut out the heart of his victim and offer it on a heated brazier to his dark god. The party decided to settle this the old-fashioned way - close combat. They easily slaughtered the band of Morlocks but the Shaman held back and fled when things began to look 'iffy.' He ordered his followers to spend their lives to defend him, then he fled. Tas broke away from the battle to chase the shaman, only to be confronted by an albino ape that the shaman had freed from its cage and set upon his pursuer.

The shaman was eventually tracked down and subdued, then taken to Squalor. Having gained the trust of Squalor, I'd envisioned them waiting until everyone was asleep then trying to sneak the Oracle out, like the scene from Return of the Jedi, but the players decided on an altogether different approach: a frontal assault. Theon attempted his signature Hold Person spell on Septimus, which failed. Enraged by this treachery, Septimus attacked Theon. During the confusion Valkrys, the monk, threw the Oracle over his shoulder and ran for it. Some very poor Intelligence checks on the part of the orc guards on the subsequent levels of Squalor's Tower allowed Valkrys's feeble and thoroughly improbable bluffs ("Everyone up to the top level - Septimus is being attacked!") to succeed beyond all expectation.

The session ended with the party fleeing Squalor's tower, strung out in order of movement rate, with an angry troll crime lord and his entire gang in hot pursuit. The plan, if I might generously refer to it as such, is to get to the upper tier - The Painted Man's domain - with the Oracle before being caught and torn limb from bloody limb by a vengeful mob of criminals.

Saturday, September 25, 2010

Roy Chapman Andrews: Real Life Pulp Hero

Having recently discussed how a dungeon delve should be planned more a like a well-equipped expedition, the American Museum of Natural History's famous Gobi expeditions of the 1920's immediately sprang to mind as an example of such an expedition.

At one time vast expanses of the world's maps were blank and labeled "here be dragons," but by the early twentieth century, most of those blank spots had been filled in. One exception was the vast Gobi in Mongolia, which was still a place of mystery to westerners.

And it was to this last frontier that the AMNH sent an ambitious expedition led by one of the greatest American explorers of the twentieth century: Roy Chapman Andrews (1884-1960).

Andrews's career began inauspiciously enough: after graduating from Benoit College in Wisconsin, he pursued his dream of working at the American Museum of Natural History. He traveled to New York to seek a position, but was informed that there were no jobs available. Andrews begged to be allowed to work at the museum in any capacity, even sweeping the floors. His passionate beseeching did, indeed, get him a job at the museum - as a janitor.

In his spare time, Andrews, already an experienced taxidermist, assisted in the collection and preparation of specimens, and he took advantage of every opportunity to learn and make himself useful while pursuing a Masters degree at Columbia University. His persistence paid off and he began to work officially as a collector for the museum - one of his first jobs was the logistically difficult task collecting and preparing a beached whale (a specimen that remains on display in the Museum to this day), which needed to be accomplished before the corpse rotted too badly to be useful.

Andrews was a larger than life figure, and he needed to be: after persuading AMNH president, Henry Fairfield Osborn to launch the Gobi expedition, Andrews was told that he would have to raise the money himself. In those days science was not supported with government funding and a successful scientist had to be adept at securing donations from wealthy philanthropists. Andrews needed $250,000 to get started, and by the end was able to secure about $5 million in current dollars from some of the wealthiest tycoons in American society including J.D. Rockefeller and Cleveland Dodge, who supplied automobiles for the expedition.

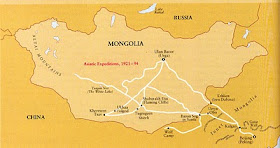

One of the largest and most ambitious scientific ventures of its day, the AMNH's Central Asiatic Expedition, as it came to be known, consisted of five treks, between 1921 and 1930, from their field headquarters in Peking into Inner and Outer Mongolia. The journeys were fraught with danger because of the 1912 fall of the Manchu Dynasty, which left China destabilized until Mao Ze Dong's rise to power in the 1940's. The expedition had the support of the Chinese government in Peking, but warlords ruled the provinces and cared little for letters of transit or other documents issued in Peking.

The situation in Mongolia was also volatile as Outer Mongolia became an independent state in 1921, and Russian Bolsheviks and Czarists battled for influence there and frequently came into conflict with the Mongols, who were, at the time, also trying to fend off territorial expansion by the Chinese. This instability resulted in a lawlessness that encouraged widespread banditry.

In one particular instance while Andrews was driving he was attacked by mounted Mongol bandits. Realizing he'd never get his car turned around in time to escape, he elected to attack, driving straight into the charging bandits with his six-shooter blazing. This was typical of Andrews who was nothing if not a decisive man of action.

These character traits, which suited him so well as an expedition leader in a lawless land was sometimes a liability in the field, however. Though Andrews had earned his Ph.D. by this time he lacked the patience for painstaking fieldwork, usually preferring to gather his specimens by shooting them. His favourite field tool for fossil collecting was a pick axe, and such was his reputation for hasty collecting that, to this day, a fossil that is damaged by careless excavation is said to have been "RCA'd." I've been guilty of RCA'ing a specimen or two in my time as well.

The wealth of scientific information and specimens that were gathered are too numerous to list here, but among the discoveries were the very first fossil dinosaur eggs ever found, which were believed at the time to have been laid by Protoceratops, but are now known to be Oviraptor eggs.

When I'm doing field work I normally have a field pouch for my notebook and pencils, and a rock hammer hanging from my belt (and sometimes pepper spray, depending on the bear situation). Notice what Andrews has on his? A gun belt and ammunition.

Roy Chapman Andrews is generally regarded as the inspiration for Indian Jones and the similarities are hard to ignore:

George Lucas has never confirmed that Andrews was a direct inspiration in the creation of Indiana Jones, and it is entirely likely that he wasn't. However, Andrews was a very popular media figure in his day and the subject of many serialized adventures in books and movies. He'd been a member of the Explorer's Club since 1908, and served as its president from 1931-1935. So even if Lucas did not consciously base Indiana Jones on Roy Chapman Andrews, it is almost certain that the character was inspired by fictional heroes that Lucas grew up with who were direct representations of Andrews:

Certainly, the life of Roy Chapman Andrews was influential in my own career path, as he represented the sort of real-life adventurer that I wanted to become and I was quite enamoured with the tales of his adventures that he recounted in his autobiography, Under a Lucky Star. It is likely that Andrews's autobiography presents a somewhat exaggerated account of his adventures, and I've read subsequent biographies of his life that tell a more balanced, and probably more realistic version of events. Still, part of me prefers the first person accounts, tainted though they may be, by personal bias. This was a guy who rose from janitor at the American Museum of Natural History to its Director from 1934 until his retirement in 1942. This was a powerful inspiration for a kid like me who grew up poor and without a lot of advantages. He lived the life of his dreams and his example encouraged generations of kids to shoot for their dreams, too.

I think the world is a more exciting place when there are real-life pulp heroes to tread the jeweled thrones of the world beneath their field-booted feet.

|

| That's not an expedition... |

|

| THIS is an expedition! (Central Asiatic Expedition near the Flaming Cliffs) |

At one time vast expanses of the world's maps were blank and labeled "here be dragons," but by the early twentieth century, most of those blank spots had been filled in. One exception was the vast Gobi in Mongolia, which was still a place of mystery to westerners.

And it was to this last frontier that the AMNH sent an ambitious expedition led by one of the greatest American explorers of the twentieth century: Roy Chapman Andrews (1884-1960).

|

| Andrews in the Mongolian badlands |

In his spare time, Andrews, already an experienced taxidermist, assisted in the collection and preparation of specimens, and he took advantage of every opportunity to learn and make himself useful while pursuing a Masters degree at Columbia University. His persistence paid off and he began to work officially as a collector for the museum - one of his first jobs was the logistically difficult task collecting and preparing a beached whale (a specimen that remains on display in the Museum to this day), which needed to be accomplished before the corpse rotted too badly to be useful.

Andrews was a larger than life figure, and he needed to be: after persuading AMNH president, Henry Fairfield Osborn to launch the Gobi expedition, Andrews was told that he would have to raise the money himself. In those days science was not supported with government funding and a successful scientist had to be adept at securing donations from wealthy philanthropists. Andrews needed $250,000 to get started, and by the end was able to secure about $5 million in current dollars from some of the wealthiest tycoons in American society including J.D. Rockefeller and Cleveland Dodge, who supplied automobiles for the expedition.

One of the largest and most ambitious scientific ventures of its day, the AMNH's Central Asiatic Expedition, as it came to be known, consisted of five treks, between 1921 and 1930, from their field headquarters in Peking into Inner and Outer Mongolia. The journeys were fraught with danger because of the 1912 fall of the Manchu Dynasty, which left China destabilized until Mao Ze Dong's rise to power in the 1940's. The expedition had the support of the Chinese government in Peking, but warlords ruled the provinces and cared little for letters of transit or other documents issued in Peking.

The situation in Mongolia was also volatile as Outer Mongolia became an independent state in 1921, and Russian Bolsheviks and Czarists battled for influence there and frequently came into conflict with the Mongols, who were, at the time, also trying to fend off territorial expansion by the Chinese. This instability resulted in a lawlessness that encouraged widespread banditry.

In one particular instance while Andrews was driving he was attacked by mounted Mongol bandits. Realizing he'd never get his car turned around in time to escape, he elected to attack, driving straight into the charging bandits with his six-shooter blazing. This was typical of Andrews who was nothing if not a decisive man of action.

|

| Out looking for trouble |

These character traits, which suited him so well as an expedition leader in a lawless land was sometimes a liability in the field, however. Though Andrews had earned his Ph.D. by this time he lacked the patience for painstaking fieldwork, usually preferring to gather his specimens by shooting them. His favourite field tool for fossil collecting was a pick axe, and such was his reputation for hasty collecting that, to this day, a fossil that is damaged by careless excavation is said to have been "RCA'd." I've been guilty of RCA'ing a specimen or two in my time as well.

The wealth of scientific information and specimens that were gathered are too numerous to list here, but among the discoveries were the very first fossil dinosaur eggs ever found, which were believed at the time to have been laid by Protoceratops, but are now known to be Oviraptor eggs.

|

| Unearthing dinosaur eggs |

When I'm doing field work I normally have a field pouch for my notebook and pencils, and a rock hammer hanging from my belt (and sometimes pepper spray, depending on the bear situation). Notice what Andrews has on his? A gun belt and ammunition.

Roy Chapman Andrews is generally regarded as the inspiration for Indian Jones and the similarities are hard to ignore:

George Lucas has never confirmed that Andrews was a direct inspiration in the creation of Indiana Jones, and it is entirely likely that he wasn't. However, Andrews was a very popular media figure in his day and the subject of many serialized adventures in books and movies. He'd been a member of the Explorer's Club since 1908, and served as its president from 1931-1935. So even if Lucas did not consciously base Indiana Jones on Roy Chapman Andrews, it is almost certain that the character was inspired by fictional heroes that Lucas grew up with who were direct representations of Andrews:

|

| Serial adventure hero based on Roy Chapman Andrews |

I think the world is a more exciting place when there are real-life pulp heroes to tread the jeweled thrones of the world beneath their field-booted feet.

Thursday, September 23, 2010

To Flee, Or Not To Flee?

Having decided to promote and encourage the employment of hirelings in my campaign, it is inevitable at some point they are going to get scared and run away. The question is, at what point?

When it comes to monster morale I usually just decide when it makes sense for them to turn tail and run, or surrender - at least when I remember to; sadly I often get caught up in the action and forget to consider things like morale, so my monsters often fight to the death more often than they ought to. But I'd prefer not to arbitrarily screw my players over by having their hirelings run away based on my own whims, so I'm going to need a morale mechanic for Swords & Wizardry.

Now, Labyrinth Lord has a nice morale mechanic and it is tempting to just swipe that to use in my S&W games, but I prefer a unified system mechanic, which in my case is rolling under an attribute score on a d20. The obvious solution is to make a Charisma check to determine whether NPCs break and run when things get tough. Of course monsters and most NPCs don't have attribute scores, nor am I inclined to bother generating them, so let's set their default morale rating at 10. This will give them a 50% chance of holding tight when all Hell breaks loose, and their morale rating can be adjusted by their controlling character's loyalty modifier based on his Charisma score. So a character with a Charisma score of 14 can, according to the S&W rules have up to 5 hirelings and has a loyalty modifier of +1, so in this case, the hirelings will have base morale rating of 11. This can be further adjusted with situational modifiers.

Monsters, too, will now have a default morale rating of 10, though exceptionally craven species might have a lower rating and unusually disciplined monsters will have a higher rating. And, just like hirelings, monsters can have their morale ratings adjusted by the loyalty modifiers based on the Charisma of bosses.

While I'm all in favour of DM adjudication, I often prefer to let the dice dictate the course of events for me, especially when the mechanic is quick and simple and can be done on the fly.

Tuesday, September 21, 2010

The Way We Play Part 2: LEGO

In a recent post I discussed some of the ways that we, as a society, have changed the way we play, from a free-form do-it-yourself style to more the structured and rigid play typical of organized sports and computer games that force us to play 'by the rules.'

I just received my Sears Christmas Wish Book in the mail today (yeah, in September, I know...) and as I was flipping through the toys I paused to carefully examine the LEGO pages and I noticed something odd: in the four pages devoted to LEGO products there was not one set of basic LEGO blocks. Everything was a themed set, many of them licensed properties like Star Wars or Toy Story, with specially-designed blocks that pretty much force you to build the picture on the box.

What the hell? This isn't LEGO, this is a model kit. What are you supposed to do with it when you're done, take it apart and build it again?

When I was a kid my best friend had an enormous collection of LEGO blocks and we used to commandeer his basement rec room and spend hours building countless creations, including fleets of invading alien spaceships, bunkers and fortresses, and just about anything else we could imagine. There was never any preconceived notion of what we were 'supposed' to build with the LEGO, it was just a whole bunch of blocks that we could use to build whatever we wanted. What ever happened to that?

I was curious; does LEGO even make basic blocks anymore? I visited the official LEGO website to find out. It turns out that they do, but finding them isn't easy. I thought I would find sets of blocks on their 'products' page, but all I got was an endless list of their sets based on licensed properties. I tried searching for 'basic blocks' but got no returns. Finally I tried shopping 'by age,' and found basic blocks on the first page of the youngest age category, 3-4 years. LEGO still makes two sets of basic blocks: the Basic Brick set has 280 pieces and the Basic Brick Deluxe set has 650 pieces. Interestingly, as you search the older age categories the Basic Brick sets appear further and further back on subsequent pages, disappearing entirely by the time you get to the 9-11 year old category. Apparently, using your imagination is only for little kids; older children aren't supposed to think for themselves - they need to be told what to build and how to play. This is the age when they need to be expanding their creativity and critical thinking skills with more sophisticated projects, not crushing it by conditioning them to play by rote.

So, are we organizing and structuring all the imagination out of our kids? I wonder what would happen if we dumped a bunch of random toys on the basement floor and told them to amuse themselves. This type of anarchic play might even lead to some of them picking up ball gloves and going outside to play for a change. One can only hope.

I just received my Sears Christmas Wish Book in the mail today (yeah, in September, I know...) and as I was flipping through the toys I paused to carefully examine the LEGO pages and I noticed something odd: in the four pages devoted to LEGO products there was not one set of basic LEGO blocks. Everything was a themed set, many of them licensed properties like Star Wars or Toy Story, with specially-designed blocks that pretty much force you to build the picture on the box.

What the hell? This isn't LEGO, this is a model kit. What are you supposed to do with it when you're done, take it apart and build it again?

When I was a kid my best friend had an enormous collection of LEGO blocks and we used to commandeer his basement rec room and spend hours building countless creations, including fleets of invading alien spaceships, bunkers and fortresses, and just about anything else we could imagine. There was never any preconceived notion of what we were 'supposed' to build with the LEGO, it was just a whole bunch of blocks that we could use to build whatever we wanted. What ever happened to that?

I was curious; does LEGO even make basic blocks anymore? I visited the official LEGO website to find out. It turns out that they do, but finding them isn't easy. I thought I would find sets of blocks on their 'products' page, but all I got was an endless list of their sets based on licensed properties. I tried searching for 'basic blocks' but got no returns. Finally I tried shopping 'by age,' and found basic blocks on the first page of the youngest age category, 3-4 years. LEGO still makes two sets of basic blocks: the Basic Brick set has 280 pieces and the Basic Brick Deluxe set has 650 pieces. Interestingly, as you search the older age categories the Basic Brick sets appear further and further back on subsequent pages, disappearing entirely by the time you get to the 9-11 year old category. Apparently, using your imagination is only for little kids; older children aren't supposed to think for themselves - they need to be told what to build and how to play. This is the age when they need to be expanding their creativity and critical thinking skills with more sophisticated projects, not crushing it by conditioning them to play by rote.

So, are we organizing and structuring all the imagination out of our kids? I wonder what would happen if we dumped a bunch of random toys on the basement floor and told them to amuse themselves. This type of anarchic play might even lead to some of them picking up ball gloves and going outside to play for a change. One can only hope.

Monday, September 20, 2010

Care and Feeding of Hirelings

Remember when hirelings used to be a staple in every adventuring party? The adventures of my youth were carefully planned affairs and much time was spent organizing a dungeon expedition, including the hiring of porters, torch-bearers, and guards, as well as mule-trains to transport the much-anticipated loot and we gathered as much lore about the dungeon and its locale as possible.

Nowadays, a small party of adventurers rides off alone into the wilderness, then ties up their horses at the dungeon entrance and heads on down without a moment's thought to logistics and then maligns their killer DM when the party wipes. Or else all concern for resource management is hand-waved away and the PCs carry on indefinitely with their adventures, never stopping to tally up the load - which probably comes to thousands of pounds per character.

Sometime betwixt then and now, D&D transformed from a game of exploration into a game of heroic fantasy. In heroic fantasy no one ever worries about trivialities such as having enough food or supplies, nor how many silk tapestries or iron-bound chests one person can reasonably carry. The shift has been gradual, and I'm not sure exactly when it started. Hirelings were definitely an important part of AD&D (1st edition, at least - I missed 2nd edition entirely). 3E has rules for hirelings, but I never once saw anyone actually use them, and 4E has cut them out of the game entirely.

My guess is that once D&D adventures started to become more about big meta-plot stories, henchmen and hirelings fell by the wayside since planning and logistics are largely unnecessary when participating in a pre-scripted storyline. This is just speculation, though, somehow the shift in play style occurred gradually enough that I didn't even notice. I just woke up one morning and said, "Hey, where did all the hirelings go?" Their absence is a glaring reminder of how much the assumptions about our hobby have changed in the last few decades.

I think a dungeon adventure should be more like a real-life expedition; well-equipped, well-manned, and well-organized. Look how many people it takes for a couple of people to make it to the summit of Mt. Everest. There aren't even any monsters after them, and they aren't collecting any treasure, but they still have a small army of porters and cooks to provide logistical support. Look also at some of the great expeditions of the early 20th century, made by museums such as the American Museum of Natural History, to remote locales such as Mongolia and Antarctica, which were led by just a few key individuals supported by a large number of support personnel.

I envision a well-organized dungeon expedition arriving at the site and establishing a well-guarded base camp to serve as a secure place to rest, recuperate and drop off treasure, followed by a thorough reconnaissance of the local area to assess the threats prior to descending into the depths. This will take enough mercenaries to adequately guard the base camp, plus a few more to accompany the exploration party into the dungeon. You'll also want enough porters to carry all the dungeon gear that you might need - rope, iron spikes, crowbars and hammers, ten-foot-poles, etc., are all bulky, heavy things. If the PCs try carrying all that stuff in addition to their armour and weapons they won't be able to move, let alone bring any loot back. Torch-bearers are important, too. Bring lots so that one mishap doesn't leave the party in pitch darkness at a critical moment. While we're at it, why not hire some specialists as well. You never know when a sage might come in handy to help decipher the ancient runes you've found all over the ominous looking Portal of Obvious Plot Device. Hirelings are cheap. Bring lots.

I've been slowly trying to introduce henchmen and hirelings to my game, but it has been difficult to overcome the inertia of years of hireling-free play. My hints and suggestions were, at first, completely disregarded and it wasn't until I switched to Swords & Wizardry, which includes hirelings in the equipment list that the players realized: "hey, we can hire help!" I interpret this as the natural reaction of players to assume that any advice the DM offers is just a devious scheme to screw them over and should be ignored unless it actually appears in the rules. Even still, it was hard to overcome player paranoia enough to get them to actually shell out the silver piece for a hireling. As one player put it, "they're just going to betray us." And so they might - if they aren't treated well. But there is no reason to assume that a well-compensated lackey won't provide reliable service.

So the first attempt to hire lackeys was conservative, to say the least. The party hired a couple of mercenaries to help fight and one guy to hold the torches and carry all of the gear. He looked like this:

This is an absolutely fantastic Reaper miniature that I fell in love with the moment I saw it. He really exemplifies the much-maligned dungeon porter and I can't help but chuckle every time I look at him.

From a DM's perspective, hirelings are great because you can show off how lethal and scary your new monster is by having it eviscerate a convenient hireling - this way you don't have to kill off a PC just to set the mood.

Now, as I mentioned, hirelings that are well-paid and cared for can usually be relied upon to provide loyal service, but even if the PCs are a bunch of tight-fisted callous bastards, they'll still find hirelings indispensable resources. One of my favourite literary examples of this is Alexandre Dumas' The Three Musketeers. Each of the Musketeers has his own lackey and they are quick to encourage young d'Artagnan to acquire one as well. If you've ever read the novel (and if you haven't, you should) you'll know that the musketeers are perpetually short on funds - they are in debt to their tailors, and landlords, and rely upon cadging free meals from acquaintances. Yet they still retain lackeys who seem never to be paid, nor particularly well treated. They are forced to sleep on the floor and are given a sound thrashing when their morale begins to wane. Whenever the musketeers do come into money it is spent on wine and getting back into the good graces of their tailors. The lackeys never get paid - yet they remain faithful and loyal servants, which is probably a commentary on living conditions in 17th century France.

Even the most dick-headed employer can find good use for disposable employees:

Mind you, once word gets out around town that your employees never seem to make it back from your expeditions it will become progressively harder to find good help, so this tactic should be used sparingly.

Let's not forget about Henchmen. The good old henchman is your personal sidekick; the Robin to your Batman, and can be counted upon to provide good and loyal service and is even competent enough to kit out with high-end gear and be kept happy. Still, there are occasions, like when you need someone to do a job, like align a communication dish in an alien-infested complex, that is just too dangerous for a PC:

Obviously, henchmen are much harder to come by the mere hirelings, so you really don't want to do this too often or you'll never get another one, but when the situation is 'him or me,' there is usually little question as to who is going to take the fall.

Nowadays, a small party of adventurers rides off alone into the wilderness, then ties up their horses at the dungeon entrance and heads on down without a moment's thought to logistics and then maligns their killer DM when the party wipes. Or else all concern for resource management is hand-waved away and the PCs carry on indefinitely with their adventures, never stopping to tally up the load - which probably comes to thousands of pounds per character.

Sometime betwixt then and now, D&D transformed from a game of exploration into a game of heroic fantasy. In heroic fantasy no one ever worries about trivialities such as having enough food or supplies, nor how many silk tapestries or iron-bound chests one person can reasonably carry. The shift has been gradual, and I'm not sure exactly when it started. Hirelings were definitely an important part of AD&D (1st edition, at least - I missed 2nd edition entirely). 3E has rules for hirelings, but I never once saw anyone actually use them, and 4E has cut them out of the game entirely.

My guess is that once D&D adventures started to become more about big meta-plot stories, henchmen and hirelings fell by the wayside since planning and logistics are largely unnecessary when participating in a pre-scripted storyline. This is just speculation, though, somehow the shift in play style occurred gradually enough that I didn't even notice. I just woke up one morning and said, "Hey, where did all the hirelings go?" Their absence is a glaring reminder of how much the assumptions about our hobby have changed in the last few decades.

I think a dungeon adventure should be more like a real-life expedition; well-equipped, well-manned, and well-organized. Look how many people it takes for a couple of people to make it to the summit of Mt. Everest. There aren't even any monsters after them, and they aren't collecting any treasure, but they still have a small army of porters and cooks to provide logistical support. Look also at some of the great expeditions of the early 20th century, made by museums such as the American Museum of Natural History, to remote locales such as Mongolia and Antarctica, which were led by just a few key individuals supported by a large number of support personnel.

I envision a well-organized dungeon expedition arriving at the site and establishing a well-guarded base camp to serve as a secure place to rest, recuperate and drop off treasure, followed by a thorough reconnaissance of the local area to assess the threats prior to descending into the depths. This will take enough mercenaries to adequately guard the base camp, plus a few more to accompany the exploration party into the dungeon. You'll also want enough porters to carry all the dungeon gear that you might need - rope, iron spikes, crowbars and hammers, ten-foot-poles, etc., are all bulky, heavy things. If the PCs try carrying all that stuff in addition to their armour and weapons they won't be able to move, let alone bring any loot back. Torch-bearers are important, too. Bring lots so that one mishap doesn't leave the party in pitch darkness at a critical moment. While we're at it, why not hire some specialists as well. You never know when a sage might come in handy to help decipher the ancient runes you've found all over the ominous looking Portal of Obvious Plot Device. Hirelings are cheap. Bring lots.

I've been slowly trying to introduce henchmen and hirelings to my game, but it has been difficult to overcome the inertia of years of hireling-free play. My hints and suggestions were, at first, completely disregarded and it wasn't until I switched to Swords & Wizardry, which includes hirelings in the equipment list that the players realized: "hey, we can hire help!" I interpret this as the natural reaction of players to assume that any advice the DM offers is just a devious scheme to screw them over and should be ignored unless it actually appears in the rules. Even still, it was hard to overcome player paranoia enough to get them to actually shell out the silver piece for a hireling. As one player put it, "they're just going to betray us." And so they might - if they aren't treated well. But there is no reason to assume that a well-compensated lackey won't provide reliable service.

So the first attempt to hire lackeys was conservative, to say the least. The party hired a couple of mercenaries to help fight and one guy to hold the torches and carry all of the gear. He looked like this:

This is an absolutely fantastic Reaper miniature that I fell in love with the moment I saw it. He really exemplifies the much-maligned dungeon porter and I can't help but chuckle every time I look at him.

From a DM's perspective, hirelings are great because you can show off how lethal and scary your new monster is by having it eviscerate a convenient hireling - this way you don't have to kill off a PC just to set the mood.

Now, as I mentioned, hirelings that are well-paid and cared for can usually be relied upon to provide loyal service, but even if the PCs are a bunch of tight-fisted callous bastards, they'll still find hirelings indispensable resources. One of my favourite literary examples of this is Alexandre Dumas' The Three Musketeers. Each of the Musketeers has his own lackey and they are quick to encourage young d'Artagnan to acquire one as well. If you've ever read the novel (and if you haven't, you should) you'll know that the musketeers are perpetually short on funds - they are in debt to their tailors, and landlords, and rely upon cadging free meals from acquaintances. Yet they still retain lackeys who seem never to be paid, nor particularly well treated. They are forced to sleep on the floor and are given a sound thrashing when their morale begins to wane. Whenever the musketeers do come into money it is spent on wine and getting back into the good graces of their tailors. The lackeys never get paid - yet they remain faithful and loyal servants, which is probably a commentary on living conditions in 17th century France.

Even the most dick-headed employer can find good use for disposable employees:

|

| "I think we should let the diggers open the case" |

Let's not forget about Henchmen. The good old henchman is your personal sidekick; the Robin to your Batman, and can be counted upon to provide good and loyal service and is even competent enough to kit out with high-end gear and be kept happy. Still, there are occasions, like when you need someone to do a job, like align a communication dish in an alien-infested complex, that is just too dangerous for a PC:

|

| "Yeah, man, Bishop should go!" |

Monday, September 13, 2010

Dungeons and Slave Girls

If you've ever been a player in one of my games then at some point you will almost certainly have encountered, and presumably rescued, a naked chick tied to an altar. If you've been playing with me for a while then you've probably experienced this more than once. It's a common theme in many of my adventures and given my predilection for dark sword & sorcery, there is going to be an element of pseudo-sexual imagery associated since sex and horror always seem to go hand-in-hand. So when you reach the climactic set-piece of one of my adventures you will likely find a power mad wizard about to sacrifice a naked chick to summon a demon:

or a bunch of crazy cultists about to sacrifice a naked chick to summon a cosmic horror:

The Abyss and the Outer Dark probably don't have a lot women, so it probably increases the chance of a successful summoning if you offer the demons a bit of cheesecake.

There is something about the imagery of a helpless woman about to be sacrificed to the powers of darkness that evokes a visceral response in people - beyond the obvious adolescent titillation - and to me, it strikes to the heart of what fantasy role playing is all about in a single, powerful image. It's almost as important as killing monsters and stealing their stuff and maybe more so, since it clearly delineates gaming then and now.

Back in the early days of D&D, when the game was more closely linked to the sword & sorcery genre, you couldn't lob a longsword without hitting a naked woman. They were frequently depicted in game manuals and were a commonplace sculpt for early miniatures. In subsequent years gaming has become more 'family-oriented' and the imagery of D&D has been cleaned up and steered away from its S&S roots and into the realm of Heroic Fantasy Suitable For All Ages.

I bought my very first miniatures on a Saturday morning in February of 1980 when I picked up a package of big-nosed goblins with floppy hats to use in my first-ever game of D&D - I was running Keep on the Borderlands later that afternoon. The package, strangely enough, included a naked female with her hands shackled above her head. I rushed home and slapped a coat of Testors enamel paint all over the miniatures, then proceeded to make my premiere foray into the world of gaming, and my first stint as DM featured the Caves of Chaos with a naked captive to rescue. This, perhaps, set the stage for all future game sessions to come.

It was hard not to buy miniatures of naked women in those days - they were really common. The fact that I couldn't even buy a pack of goblins without the obligatory naked chick speaks volumes about how the game was played back then. Another example, of course, is the cover of D&D Supplement 3: Eldritch Wizardry.

It's hard to imagine TSR using an image like that by the mid-80's. Compare the cover illustration of 1976's Eldritch Wizardry to this image from the 1981 module B3 Palace of the Silver Princess:

According to Gary Gygax, TSR executives (whom he referred to, I believe, as 'twits') wigged out when they saw this picture and removed it from subsequent printings - the 'twits' even went so far as to search the desks of TSR employees to confiscate any existing copies.

Ironically, as nudity was excised from role playing games it became a lot more prevalent in mainstream media. Back in the early '80's I could buy miniatures of naked women and game books like Eldritch Wizardry, but I couldn't go to see Conan the Barbarian, which was X-rated. Nowadays, while it is deemed inappropriate to depict nudity in game products, kids can see shows on prime-time T.V. that are far racier than anything in the Conan movie. When I was a kid I used to have to stay up until 2:00 a.m. watching the CBC French channel to catch a fleeting glimpse of breast - kids today can see much more than that well before bed time. I don't know what, if anything, this means, but the dichotomy is interesting, as is the change in the genre tropes of fantasy role playing.

Gaming may have diverged from its Sword & Sorcery roots long ago, but in the den of iniquity that is my basement, it is still 1974: wizards are sinister, cultists are crazy, and women are naked. And unsurprisingly, that's the way my players like it. The imagery is as powerful today as it was thirty-five years ago.

or a bunch of crazy cultists about to sacrifice a naked chick to summon a cosmic horror:

The Abyss and the Outer Dark probably don't have a lot women, so it probably increases the chance of a successful summoning if you offer the demons a bit of cheesecake.

There is something about the imagery of a helpless woman about to be sacrificed to the powers of darkness that evokes a visceral response in people - beyond the obvious adolescent titillation - and to me, it strikes to the heart of what fantasy role playing is all about in a single, powerful image. It's almost as important as killing monsters and stealing their stuff and maybe more so, since it clearly delineates gaming then and now.

Back in the early days of D&D, when the game was more closely linked to the sword & sorcery genre, you couldn't lob a longsword without hitting a naked woman. They were frequently depicted in game manuals and were a commonplace sculpt for early miniatures. In subsequent years gaming has become more 'family-oriented' and the imagery of D&D has been cleaned up and steered away from its S&S roots and into the realm of Heroic Fantasy Suitable For All Ages.

I bought my very first miniatures on a Saturday morning in February of 1980 when I picked up a package of big-nosed goblins with floppy hats to use in my first-ever game of D&D - I was running Keep on the Borderlands later that afternoon. The package, strangely enough, included a naked female with her hands shackled above her head. I rushed home and slapped a coat of Testors enamel paint all over the miniatures, then proceeded to make my premiere foray into the world of gaming, and my first stint as DM featured the Caves of Chaos with a naked captive to rescue. This, perhaps, set the stage for all future game sessions to come.

It was hard not to buy miniatures of naked women in those days - they were really common. The fact that I couldn't even buy a pack of goblins without the obligatory naked chick speaks volumes about how the game was played back then. Another example, of course, is the cover of D&D Supplement 3: Eldritch Wizardry.

It's hard to imagine TSR using an image like that by the mid-80's. Compare the cover illustration of 1976's Eldritch Wizardry to this image from the 1981 module B3 Palace of the Silver Princess:

According to Gary Gygax, TSR executives (whom he referred to, I believe, as 'twits') wigged out when they saw this picture and removed it from subsequent printings - the 'twits' even went so far as to search the desks of TSR employees to confiscate any existing copies.

Ironically, as nudity was excised from role playing games it became a lot more prevalent in mainstream media. Back in the early '80's I could buy miniatures of naked women and game books like Eldritch Wizardry, but I couldn't go to see Conan the Barbarian, which was X-rated. Nowadays, while it is deemed inappropriate to depict nudity in game products, kids can see shows on prime-time T.V. that are far racier than anything in the Conan movie. When I was a kid I used to have to stay up until 2:00 a.m. watching the CBC French channel to catch a fleeting glimpse of breast - kids today can see much more than that well before bed time. I don't know what, if anything, this means, but the dichotomy is interesting, as is the change in the genre tropes of fantasy role playing.

Gaming may have diverged from its Sword & Sorcery roots long ago, but in the den of iniquity that is my basement, it is still 1974: wizards are sinister, cultists are crazy, and women are naked. And unsurprisingly, that's the way my players like it. The imagery is as powerful today as it was thirty-five years ago.

Thursday, September 9, 2010

Touch-downs, Home-runs, and House-rules

I was recently chatting with my sister-in-law, whose two oldest boys were in hockey camp. The oldest of the two (13 years old) had team try-outs later that week and if he made the team it would cost $2000.00 in fees. I almost choked on my coffee. Two grand for a 13-year-old to play hockey? For one season? This didn't include the cost of equipment which, at that age, would need to be replaced annually given how fast adolescent boys grow, fund-raising bingos that would need to be worked, or the countless hours chauffeuring the kids to and from games and practices. This is was completely outside my experience of playing hockey as a kid.

Like most Canadian kids I grew up with a hockey stick in hand, but back then they were made of wood and inexpensive. I played on the street with a foam puck and my goal posts were blocks of ice that needed to be replaced every five or ten minutes after a car drove over one of them. And I certainly didn't need to 'try out' to be on any team, I just grabbed my stick and went outside; there was almost always a pick-up game going on that needed another player. Consequently, I didn't play once or twice a week, I played pretty much every day all winter long. Of course everyone took their sticks to school and we played on the rink at recesses and lunch hour, too. The best thing about such 'disorganized sport' was that no one really cared how good you were and you never got screamed at for missing a shot or letting one through. Hell, half the time we didn't even keep score - we were playing for fun.

The same went in the summer, when I played softball every day. Again, I wasn't part of any team - I'd just grab my glove and head to the playground. There was always a group of my friends waiting for enough kids to show up to get a game going. In autumn, the game de jour switched to touch football or, to be more accurate in our case, bone-jarring-shove football, which frequently escalated into full-body-slam football.

What these three games had in common was a very loose adherence to the rules. Due to the vagaries of environment and players we had to modify the games and make up rules to make them work. Our touch football games were especially heavily house-ruled, and were a bizarre fusion of Canadian and American rules plus our own made up stuff. It was a bit like Calvin-ball.

House rules were an intrinsic part of all of our seasonal pick-up games and I doubt very much that the way our group played any given sport was even remotely similar to the way another group might play it. Kind of like D&D back in the early days.

It's a popular pastime among the old-school community to debate when, exactly, D&D 'went wrong,' with the finger of blame commonly pointed at Dragon Lance. But I wonder if there aren't broader cultural issues at play. Have we, as a society, profoundly changed the way that we play over the last couple of decades?

Old school D&D was all about free-form 'sandbox' play and a do-it-yourself mentality, but really, isn't that the way we played everything back then? I played a lot of boardgames as a child, such as Monopoly, Payday, Clue, Life, etc. and my friends and I invariably made up our own rules for these games as well - we always had more fun that way. Given the unstructured way that we played everything then, is it any wonder that we would approach D&D any differently?

I don't see kids playing pick-up games anymore. Halfway through writing this post I paused to take my daughter, Elena, to the playground across the street from our house; it is a beautiful evening and a perfect night to toss a football around. When I was a kid that park would have been packed on a night like this and every kid in the neighborhood would be out after supper, trying to milk the juice out of every last minute of summer. But the park was deserted, as it always is. Never once, in the seven years that I have lived here have I seen a single pick-up game of anything played in the park or on the streets. No one does it anymore - at least not around here. Kids today only seem to play organized sports. Likewise, I doubt Monopoly et al is as popular with today's kids as it was with my generation. Today, it seems, kids play their games on computers or consoles.

What's the common thread here? Structure. We have a generation of kids playing games and sports that are structured and have intractable rules and methods of play. They couldn't change them if they wanted to, but I'm not sure if it would even occur to anyone to make up their own rules anymore - it simply isn't part of contemporary culture. Maybe this is why we are seeing rules-heavy role playing games, like 4E, that take the GM out of the equation by limiting his creative control and ability to adjudicate play. Maybe today's rpgs are simply a reflection of the way that today's gamers have grown up playing, just as old-school rpgs reflect the way people played back then. I think this might also explain why so many of us in the old-school community find 'new-school' rpgs and their philosophies so objectionable - they are completely contrary to all of our past experiences - inimical to our very concept of 'play.'

I fear that playing in such structured environments may be irrevocably damaging the imagination and creativity of today's children, and it saddens me to walk through the park and not see anyone playing in it. On an encouraging note, however, my daughter's current favourite game is 'reverse snakes and ladders,' which is her own house-ruled version in which we start at the top of the board, go up snakes and down ladders. It isn't a huge divergence, but she's only four years old, and it's a start.

Like most Canadian kids I grew up with a hockey stick in hand, but back then they were made of wood and inexpensive. I played on the street with a foam puck and my goal posts were blocks of ice that needed to be replaced every five or ten minutes after a car drove over one of them. And I certainly didn't need to 'try out' to be on any team, I just grabbed my stick and went outside; there was almost always a pick-up game going on that needed another player. Consequently, I didn't play once or twice a week, I played pretty much every day all winter long. Of course everyone took their sticks to school and we played on the rink at recesses and lunch hour, too. The best thing about such 'disorganized sport' was that no one really cared how good you were and you never got screamed at for missing a shot or letting one through. Hell, half the time we didn't even keep score - we were playing for fun.

The same went in the summer, when I played softball every day. Again, I wasn't part of any team - I'd just grab my glove and head to the playground. There was always a group of my friends waiting for enough kids to show up to get a game going. In autumn, the game de jour switched to touch football or, to be more accurate in our case, bone-jarring-shove football, which frequently escalated into full-body-slam football.

What these three games had in common was a very loose adherence to the rules. Due to the vagaries of environment and players we had to modify the games and make up rules to make them work. Our touch football games were especially heavily house-ruled, and were a bizarre fusion of Canadian and American rules plus our own made up stuff. It was a bit like Calvin-ball.

House rules were an intrinsic part of all of our seasonal pick-up games and I doubt very much that the way our group played any given sport was even remotely similar to the way another group might play it. Kind of like D&D back in the early days.

It's a popular pastime among the old-school community to debate when, exactly, D&D 'went wrong,' with the finger of blame commonly pointed at Dragon Lance. But I wonder if there aren't broader cultural issues at play. Have we, as a society, profoundly changed the way that we play over the last couple of decades?

Old school D&D was all about free-form 'sandbox' play and a do-it-yourself mentality, but really, isn't that the way we played everything back then? I played a lot of boardgames as a child, such as Monopoly, Payday, Clue, Life, etc. and my friends and I invariably made up our own rules for these games as well - we always had more fun that way. Given the unstructured way that we played everything then, is it any wonder that we would approach D&D any differently?

I don't see kids playing pick-up games anymore. Halfway through writing this post I paused to take my daughter, Elena, to the playground across the street from our house; it is a beautiful evening and a perfect night to toss a football around. When I was a kid that park would have been packed on a night like this and every kid in the neighborhood would be out after supper, trying to milk the juice out of every last minute of summer. But the park was deserted, as it always is. Never once, in the seven years that I have lived here have I seen a single pick-up game of anything played in the park or on the streets. No one does it anymore - at least not around here. Kids today only seem to play organized sports. Likewise, I doubt Monopoly et al is as popular with today's kids as it was with my generation. Today, it seems, kids play their games on computers or consoles.

What's the common thread here? Structure. We have a generation of kids playing games and sports that are structured and have intractable rules and methods of play. They couldn't change them if they wanted to, but I'm not sure if it would even occur to anyone to make up their own rules anymore - it simply isn't part of contemporary culture. Maybe this is why we are seeing rules-heavy role playing games, like 4E, that take the GM out of the equation by limiting his creative control and ability to adjudicate play. Maybe today's rpgs are simply a reflection of the way that today's gamers have grown up playing, just as old-school rpgs reflect the way people played back then. I think this might also explain why so many of us in the old-school community find 'new-school' rpgs and their philosophies so objectionable - they are completely contrary to all of our past experiences - inimical to our very concept of 'play.'

I fear that playing in such structured environments may be irrevocably damaging the imagination and creativity of today's children, and it saddens me to walk through the park and not see anyone playing in it. On an encouraging note, however, my daughter's current favourite game is 'reverse snakes and ladders,' which is her own house-ruled version in which we start at the top of the board, go up snakes and down ladders. It isn't a huge divergence, but she's only four years old, and it's a start.

Monday, September 6, 2010

Creature Feature: Brine Ghouls

Jacobi quickened his pace as the old coast road entered the salt marsh. Daylight was fading fast, and folks had been disappearing from this stretch of road of late. He stopped short and held his breath when he heard a splash off to his left. He counted several long seconds before exhaling in relief.

"Probably just a frog," he told himself, chuckling, "no need to jump at every croak and cricket chirp 'twixt here and home."

Just then a horror from Jacobi's worst nightmares erupted from the water, its long grasping fingers reaching for his throat. The foetid creature smelled like rotting fish, and slimy seaweeds hung like hair from its bald scalp as it bore him backwards into the water. Jacobi struggled in vain against the thing's preternaturally wiry strength and, slowly, his head was forced underwater as his struggles began to weaken. Looking up through the water, the last thing Jacobi saw before the darkness took him was the thing's baleful yellow eyes and the leering maw full of sharp, pointed teeth looming in front of his face.

Ghoul, Brine

Armour Class: 6 Special: Camouflage

Hit Dice: 2 Move: 9" (6" swim)

Attacks: Claws, or Strangle HDE/XP: 3/60 xp

A Brine Ghoul may attack with both claws, making a single attack with a +1 bonus to hit, or may attempt to strangle its victim. If it hits with its strangle attack it wraps its hands around the victim's throat dealing 1d6 damage; it then throttles its victim, automatically dealing 1d6 damage each round unless its opponent can break free by making a strength check.

Camouflage: Brine Ghouls are very hard to see when they are submerged and may ambush prey, automatically gaining surprise in the first round of combat.

Brine Ghouls are found in coastal regions, salt marshes, and estuaries. They are created when someone is murdered by drowning under a new moon. The murder victim later rises as a Brine Ghoul, full of spite and hatred for the living. They attempt to drag any living humanoid they find down to the depths to share its fate. Anyone drowned by a Brine Ghoul will rise as one the very next night; thus, large packs of them can form very quickly.

The concept of the Brine Ghouls arose while I was trying to figure out a colour scheme for a box of Warhammer Crypt Ghouls that had been donated to the game by one of my players. I'd painted up four or five with different and, for the most part, fairly traditional ghoul colours, except for one that had a bluish, blood-drained look about it. I asked my wife which one she like best, and much to my surprise she actually gave me some positive feedback. Now, usually, whenever I try to solicit my wife's opinion about my painting she always says "it's very nice dear," in the same tone I sometimes use with my four year old daughter when she's doing something silly. This time, though, she pointed to the bluish ghoul and said it looked like it was climbing out of the water or something.

Bing! A light bulb went on and gave me the idea for a type of aquatic ghoul with a blue-green paint scheme. I also told my wife that I would expect similar constructive comments in the future rather than the usual condescending pat on the head. We'll see.

"Probably just a frog," he told himself, chuckling, "no need to jump at every croak and cricket chirp 'twixt here and home."

Just then a horror from Jacobi's worst nightmares erupted from the water, its long grasping fingers reaching for his throat. The foetid creature smelled like rotting fish, and slimy seaweeds hung like hair from its bald scalp as it bore him backwards into the water. Jacobi struggled in vain against the thing's preternaturally wiry strength and, slowly, his head was forced underwater as his struggles began to weaken. Looking up through the water, the last thing Jacobi saw before the darkness took him was the thing's baleful yellow eyes and the leering maw full of sharp, pointed teeth looming in front of his face.

Ghoul, Brine

Armour Class: 6 Special: Camouflage

Hit Dice: 2 Move: 9" (6" swim)

Attacks: Claws, or Strangle HDE/XP: 3/60 xp

A Brine Ghoul may attack with both claws, making a single attack with a +1 bonus to hit, or may attempt to strangle its victim. If it hits with its strangle attack it wraps its hands around the victim's throat dealing 1d6 damage; it then throttles its victim, automatically dealing 1d6 damage each round unless its opponent can break free by making a strength check.

Camouflage: Brine Ghouls are very hard to see when they are submerged and may ambush prey, automatically gaining surprise in the first round of combat.

Brine Ghouls are found in coastal regions, salt marshes, and estuaries. They are created when someone is murdered by drowning under a new moon. The murder victim later rises as a Brine Ghoul, full of spite and hatred for the living. They attempt to drag any living humanoid they find down to the depths to share its fate. Anyone drowned by a Brine Ghoul will rise as one the very next night; thus, large packs of them can form very quickly.

The concept of the Brine Ghouls arose while I was trying to figure out a colour scheme for a box of Warhammer Crypt Ghouls that had been donated to the game by one of my players. I'd painted up four or five with different and, for the most part, fairly traditional ghoul colours, except for one that had a bluish, blood-drained look about it. I asked my wife which one she like best, and much to my surprise she actually gave me some positive feedback. Now, usually, whenever I try to solicit my wife's opinion about my painting she always says "it's very nice dear," in the same tone I sometimes use with my four year old daughter when she's doing something silly. This time, though, she pointed to the bluish ghoul and said it looked like it was climbing out of the water or something.

Bing! A light bulb went on and gave me the idea for a type of aquatic ghoul with a blue-green paint scheme. I also told my wife that I would expect similar constructive comments in the future rather than the usual condescending pat on the head. We'll see.

Saturday, September 4, 2010

Advice Sought

I'm hoping that someone with stronger Bloggerfu than mine can help me out with some advice. I'm unable to post comments on blogs that require you to select a profile from a drop-down list. I've tried selecting my Google account, my Wordpress account, Name/URL, and anonymous and nothing works. When I post the comment it just disappears into the aether.

While I have no problem posting comments on blogs that use the same comment form as I do on this blog, I've never been able to post comments on the 'select a profile' type of comment form, and since they seem to becoming more and more common, I'd really like to find out what I'm doing wrong.

Anyone know what's going on here or have any suggestions?

Thanks!

While I have no problem posting comments on blogs that use the same comment form as I do on this blog, I've never been able to post comments on the 'select a profile' type of comment form, and since they seem to becoming more and more common, I'd really like to find out what I'm doing wrong.

Anyone know what's going on here or have any suggestions?

Thanks!

Friday, September 3, 2010

More on Imagery

In my last post, I commented that a picture trumps a thousand words, but I don't think I realized just how true that was until I had time to think about a comment that was made about the depiction of dwarfs in the Lord of the Rings movies. I don't know how many times I've read the Lord of the Rings trilogy, but it has been a lot - certainly far more times than I've watched the movies. I first read it when I was eleven years old and have re-read it many times since then. I read it again last year and I was shocked at how many things that I thought were in the book were not. My false memories were scenes imprinted in my brain from watching the movies.

It is odd, and a bit disturbing, that the movies, which I have watched only a few times have over-written my memories of a book that I have read many, many times. This goes to show just how visually attenuated our brains are, that my memories can be altered by a few images. This also makes me wonder how people perceive stories when they see them first as movies and only later read them. Will they ever truly see and internalize the scenes described in the book, or will their minds automatically default to the cinematic portrayal? I have quite a few movies in my DVD collection that are adaptations of books that I love: Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, The Last of the Mohicans, and Master and Commander, just to name a few. I'm reluctant to let my daughter watch any of these movies until she's had a chance to experience the books. Is it possible to truly appreciate a work of literature after your mind has been imprinted with the Hollywood version?

This leads me to wonder: do movies based upon books have any artistic value or do they just seduce us down the path of intellectual laziness? Do they stab blazing fiery pokers in our mind's eyes, forever blinding them and killing our imagination? This is not an indictment of all movies; original screenplays tell stories intended to be viewed on the big screen, and there are many of these that I love. But I've yet to see an adapted screenplay that was anywhere near as good as the book that inspired it. Sure it was neat to see the Battle of Helm's Deep, or the Battle of Pelennor Fields on the big screen, but I'd already seen these battles played out in my imagination many times before and I'm not sure that a movie, no matter how sophisticated its visual effects, can ever match that.

I've always acknowledged that visual media play an important role in my imaginary creations, and I've said before that the story boards of my games are always painted in my mind's eye by Frank Frazetta, but I think we need to be careful about what images we view because, as I said, a picture can trump a thousand words and the wrong picture can do a lot of harm.

A few years ago I hired an artist to illustrate all of the new fossil taxa that I described in my book on the Cambrian brachiopods of South Dakota, and it was a painstaking process to ensure that all of the illustrations were exactly perfect. I always felt guilty about making the poor artist redraw pictures several times over until every detail was correct and in perfect proportion. Professional scientific illustrators are used to this, though, and understand the need to get the drawing exactly right. I know, that no matter how thoroughly and exhaustively I described the species, it would all be undone by a single inaccurate illustration because the picture, not the words, is what will stick in people's heads. I doubt very much that this much care and attention is given to cinematic adaptations of literary works.